Words

The teacher’s role during independent writing should not be that of a walking spelling dictionary for students. Encouraging children to say the word they want to write slowly, to hear the sequence of sounds, and to try to write the word fosters independence. Children soon realize there are alternative ways of getting to new words that do not depend on memorizing spelling or asking the teacher how to write a word. Additionally, as they observe the teacher during demonstrations of spelling strategies during interactive writing, their skill in segmenting the sounds and making letter/sound connections becomes stronger. Going from sounds to letters is easier for the child than letters to sounds (sic)(Clay, 1993). The first is done in a meaningful, authentic writing task that makes sense to the child. The second is often done in isolation which makes it more difficult for the child to apply to reading or writing.

Allowing for approximations in their spelling also encourages independence as the child can move on with the writing process. The teacher or other students can help later with spelling strategies or resources for finding needed words.

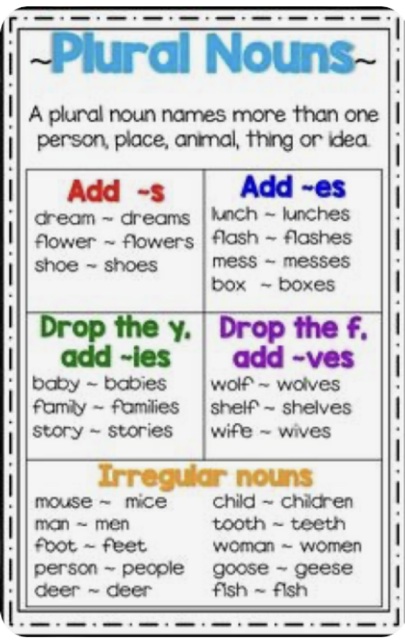

There are words that need to become sight words because they appear frequently in reading and are often needed in writing. These words can be taught during the interactive writing lesson as they come up. Not only are these core words necessary, but they are also needed by the child to generate other words. Clay (1993) asserts that, “As the core of known words builds in writing, and the high frequency words become known, these provide a series from which other words can be composed taking familiar bits from known words and getting to new words by analogy” (p. 244).

The teacher shows the children the new word as she slowly writes each sound. The children then practice “writing” it in the air and on the rug several times. When the word taught comes up again, it is reviewed in this multisensory way. Multiple exposures through repeated readings and opportunities to practice writing the new word increases familiarity. As the word is read over and over, it becomes more solid.

When students are ready to generate new words from known words, this is demonstrated on a whiteboard or Magadoodle or with magnetic letters showing how changing a part of a known word can generate new words (can/candy, see/trees, out/cloud). Once again, the teacher must demonstrate how this is a problem-solving strategy children is useful for reading and writing.

Reading the Room

A classroom with interactive writing charts displayed around the room surrounds children with meaningful and authentic print. These charts become resources for interactive writing lessons as the teacher and students make connections to previous learning related to a topic or to a word, letter, or cluster of letters.

Student names are useful when learning how words work. They contain common patterns found in many words. A classroom name chart serves to link sounds with letters or clusters of letters. The teacher provides clear demonstrations in how to use the name chart to find needed letters, sounds, or word parts for writing. Kindergarten begins with a chart with students’ first names. Gradually the chart is replaced with one listing first and last names. In first and second grade a chart with students’ first, middle, and last names provides most all the letter patterns found in words. Placing these charts close to the area where interactive writing lessons take place makes it easy for the teacher to demonstrate a link between a words needed in writing to a part in a name (Wiley, 1998).

A word wall (Cunningham, 1995) placed strategically near the interactive writing area allows further connections in finding known high frequency words or using these words to teach phonics through analogy (“’See’ has the double ‘ee’ that we need in the word ‘keep.’”). As new high frequency words are learned, they are added to the word wall at that time. Reading the room, a few charts each day, allows for more teaching opportunities and solidifies students’ word knowledge.

The reciprocity of reading and writing is clearly demonstrated when pools of knowledge in reading and writing are linked through teacher demonstrations (Clay, 1993). The classroom displays of interactive writing charts become clear records of related learning experiences in the interactive writing sessions useful to the students as they read and write.

Clay, M. (1993). Becoming literate. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Clay, M. (1995). Reading recovery: A guidebook for teachers in training. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Clay, M. (1997). What did I write? Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Cunningham, P. M. (1995). Phonics they use: Words for reading and writing. New York: Harper Collins.